DO VICE PRESIDENTS “ACCOMPLISH” ANYTHING?

My rankings of Vice Presidents — from best to worst — may surprise you.

My friend, Arbella Azizian raised an interesting question with me in a discussion recently about Vice Presidents — both past and present. She shared her perspective that most Vice Presidents don’t do much in terms of either policy or leadership. Hers was a non-partisan point of view, meant to apply to the Vice Presidents of both political parties.

I pondered this point of view. This topic is certainly timely, because it came up right after J.D. Vance was chosen as Donald Trump’s running mate. And soon, we’re likely to learn who Kamala Harris (and Democrats) will select as their veep candidate. It also matters because the current serving VP is now running for President.

Have any Vice Presidents really mattered? Does the office weild any power or mean anything? It’s easy to say — no. However, some Vice Presidents have wielded significant influence. A few have altered history in a negative way.

Let’s ignore the obvious fact that Vice Presidents are only a heartbeat away from the top job and that several have moved into the Oval Office when Presidents died.

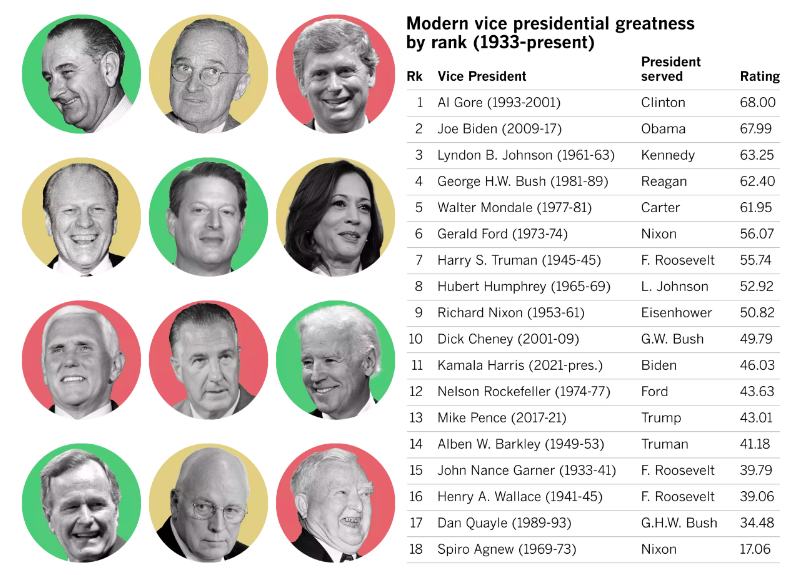

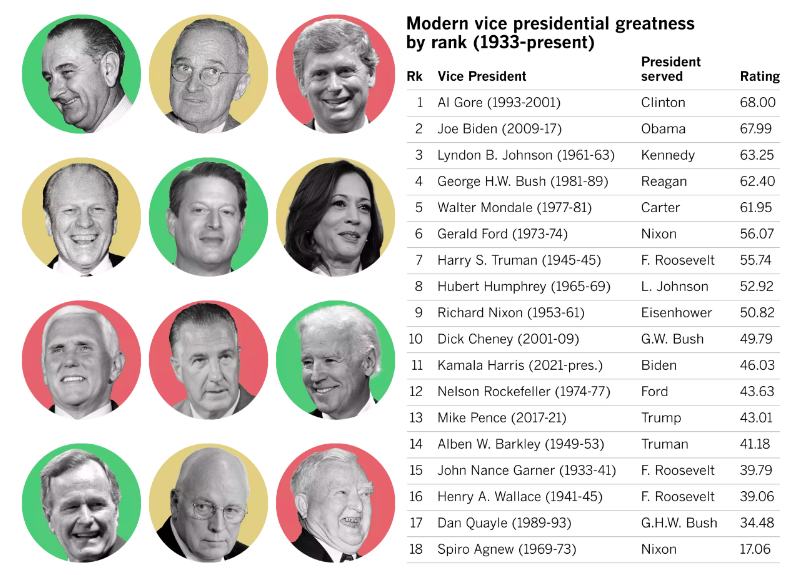

Accordingly, what follows are my rankings of Vice Presidents of the modern political era, listed best-to-worst.

Important: These rankings have nothing to do with policies or partisanship, or my opinions thereof. I’m ranking accomplishments and impacts while serving as Vice President only, irregardless of the positives or negatives of their decisions and actions. These rankings also don’t take into account what Vice Presidents did either before or after serving in office.

Note: Before proceeding, here’s a recent ranking by historians (CLICK LINK HERE TO READ MORE):

Now, here’s my list and analysis:

1. Dick Cheney — George W. Bush’s veep from 2001-2009 was the most powerful and influential Vice President in history, and it’s not even close. Cheney was a virtual “Co-President” given the enormous role in played in personnel decisions and executive policies–both domestic and foreign. Cheney was one of the key architects of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars (and subsequent occupations). Insiders also point to Cheney assuming the role as Bush’s “filter,” a virtual gatekeeper of information and staff that ultimately went to the President. He was Bush’s primary public spokesman on all matters of policy. He was on the news talk shows more than any other public figure. Cheney’s background as Congressman, Chief of Staff, and Secretary of Defense made him an essential component of the Bush Presidency who, history shows, was heavily involved in every decision that came out of the Oval Office.

2. Al Gore — Bill Clinton’s veep from 1993-2001 ranks high as an effective and influential second-in-command. Like Clinton, Gore was an energetic and youthful leader (43 when he assumed office) who was very active in advancing the Administration’s agenda. Gore previous role as Senator combined with a lifetime of Washington experience made him Clinton’s second-closest advisor (behind Hillary), going after issues including government waste and fraud, promoting the development of information technology, and advancing environmental initiatives. Gore also came out of the Clinton scandal’s unscathed which is also worth noting.

3. Richard Nixon — Dwight Eisenhower’s veep is tough to rank for obvious reasons. But let’s dismiss Nixon’s obvious baggage, and focus instead on his eight years within the Administration — 1952-1961. It’s important to remember Eisenhower suffered a heart attack that left him unable to perform his duties. So, Nixon stepped in and showed quiet leadership during the nearly two months of recuperation. Impressed, Eisenhower who had considered dropping Nixon off the ticket in the 1956 re-election, decided to keep him. In his second term, Nixon was tasked with roles varying from goodwill ambassador abroad to campaign advisor at home. Nixon also developed relationships with Soviet leaders that would be important years later during Detente (he was the first top American official to visit the USSR, and later welcomed and hosted Nikita Khrushchev when he toured the US in 1959. Also recall Nixon’s meeting with Fidel Castro that same year, right after the Cuban Revolution that might have altered history had Nixon won the 1960 election. I say Nixon is tough to rank because Eisenhower didn’t like Nixon, and insulted him on occasion — which either elevates or reduces Nixon’s place in 1950’s American politics, depending upon one’s perspective.

4. Mike Pence — Donald Trump’s veep is another who’s difficult to judge. Operating within the non-stop chaos of the Trump White House must have challenging, so credit Pence who provided some degree of sanity and normalcy. Pence’s public role during the COVID crisis was also admirable, juggling Trump’s inane lies and lunacy with actual governance and leadership behind the scenes. Pence was tasked with searching for and implementing COVID treatment and appeared to carry out his duties admirably. Let’s also remember Pence’s commitment to Constitutional principles when things mattered most, on the day of Trump’s Jan. 6th insurrection. It might not be a stretch to say Pence helped to save American democracy.

5. George H.W. Bush — Serving in Ronald Reagan’s shadow for two terms could not have been easy. Bush Sr. was clearly capable of wielding the levers of power, but never allowed his ambition or ego to outshine the President. Bush Sr. was a near perfect support staffer and advisor, though it’s also difficult to point to any specific accomplishments or policies he advanced in the period 1981-1989.

6. Joe Biden — When Barack Obama was initially elected in 2008, he didn’t have much Washington experience. Hence, he picked an established 35-year veteran insider legislator as his veep choice and Biden turned out to be an ideal pick over two terms. Much like Bush Sr., Biden wasn’t going to ever outshine the President, nor be credited with much other than personal loyalty by serving strictly in an advisory capacity.

7. Walter Mondale — The former Minnesota Senator served as Jimmy Carter’s veep 1977-1981. Like many other ex-governors (who had been outsiders), Carter pegged an experienced legislator as his running mate, who presumably would be helpful in navigating the political scene. Remembering anything specific from Mondale’s service as Vice President is difficult, especially in light of Carter’s Administration shortcomings, which was fraught with challenges–both domestic and foreign. An average midddle-of-the-road grade seems appropriate here.

8. Lyndon Johnson — LBJ was one of the great Senate Majority Leaders in history and later one of the most consequential Presidents of the 20th Century who posted a stellar record of achievements on domestic policy. However, his three-plus years as Vice President during the Kennedy Administration were a self-described wasteland. This was the most depressing era of Johnson’s political career, excluded from most Kennedy policy decisions. LBJ was selected to the national ticket strictly as a political compromise, and given the Kennedy Administration’s relatively few accomplishments (I rank JFK as the most overrated President of all time), pointing to any accomplishments by Johnson as veep is futile. Johnson was a great leader in so many ways, but clearly the wrong man for this job.

9. Hubert Humphrey — Given LBJ’s sweeping mid-1960’s domestic agenda, which was the most impactful presidency of my lifetime (civil rights, immigration reform, introduction of Medicare, etc.), one would expect the Vice President to receive some of the credit. However, most historians note that LBJ personally was the driving force behind the Great Society (just listen to the tapes of countless phone calls from the Oval Office). VP Humphrey played only a minimal role in crafting and advancing Johnson Administration policy and probably would have been far more effective had he continued serving in the Senate, where he was widely respected as a leader on progressive causes.

10. Gerald Ford — Ford ranks low on this list, not because of any personal misdeeds. Rather, he simply did play much of a role as he was in office only eight months and his entire tenure was consumed by the Watergate scandal and constant scrutiny of President Nixon. Fortunately, Ford remained unscathed by Watergate and historians praise him for his calmness and stabilizing influence following Nixon’s resignation. That said, it’s impossible to think of a single accomplishment or much of anything from Vice President Ford.

11. Nelson Rockefeller — Many Americans forget “Rocky” was Ford’s veep for nearly two years, 1974-1977. Rockefeller’s selection was largely viewed as a political payback for many years of public service. Rockefeller served as New York Governor for four terms, which were tumultuous times, but his tenure as Vice President is now largely forgotten. Also note that Ford later picked Robert Dole as his veep in the 1976 election, discarding Rockefeller who was politically inconsequential.

12. Dan Quayle — Vice President Quayle gets maligned for a number of gaffes and public missteps, which provided lots of fodder for comedians during 1989-1993, when he served. Quayle was initially selected for his youthful energy but never gained much traction as a communicator or someone with enough experience to advance Bush Administration policies. Some of the criticism is probably unfair, but Quayle was clearly a drag on Bush Sr.’s presidency and ineffective in the role as veep.

13. Spiro Agnew — Nixon’s veep was one of only two in American history to resign from office in disgrace. He was charged and convicted of bribery and tax evasion, in crimes unrelated to Watergate. Agnew was a puzzling Vice Presidential choice from the start, bringing no constituency, political contacts, knowledge, or experience to the Nixon presidency. Review the infamous Nixon tapes, containing hundreds of hours of recorded conversations, and Agnew’s voice is barely heard on any of them. He had virtually no influence nor advisory capacity to Nixon, even on his accomplishments. Utterly without charisma, politically dumb, inconsequential, and corrupt, by any measure Spiro Agnew ranks as the worst Vice President in history.

In summation, returning to the original question — I hereby conclude the answer as to Vice Presidential “accomplishments” varies widely. Most terms are indeed inconsequential, but there are also a few who have been quite impactful on history–both positively and negatively.

__________

Note: Current Vice President Kamala Harris is not ranked.

Read More